Systematic Review on the Efficacy of Atrial Fibrillation Screening Using Wearable Devices

-

摘要:

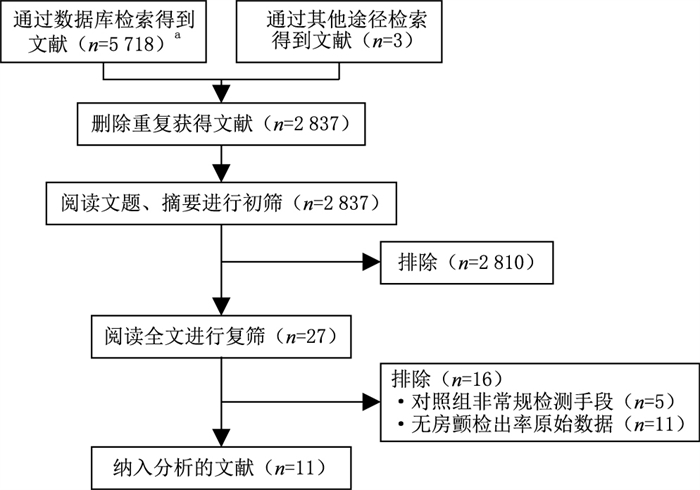

目的 采用系统评价的方法,分析随机对照试验(RCT)研究中不同种类可穿戴设备用于房颤筛查的实际检出率,为能显著有效提升房颤检出率设备的临床应用提供综合证据。 方法 检索MEDLINE(PubMed)、Ovid、Clinical Trials、万方医学网和中国知网数据库,筛查出建库至2021年10月30日所有符合本文主题的RCT论文,按照系统评价和meta分析的优先报告条目,提取出与房颤检出率相关的数据,进行归纳整理分析。 结果 纳入RCT原始论文11篇,合计意向受试人数41 565人。有5个RCT均证明,连续心电图(cECG)技术类的胸贴与常规检测手段相比显著地提升了房颤的检出率。在6个关于手持式间歇性ECG检测设备的RCT研究中,只有2个证实了房颤检出率的显著提升。 结论 cECG胸贴比常规检测手段可以更有效地筛查出房颤。手持式间歇ECG检测设备的房颤筛查效果尚不一致,有待进一步研究。 Abstract:Objective To carry out a systematic review of randomised controlled trial (RCT) studies on atrial fibrillation (AF) detection rates by wearable devices and provide the integrated evidence in supporting the clinical application of wearable devices that have been shown to be significantly effective in enhancing AF detection rates. Methods MEDLINE (PubMed), Ovid, Clinical Trials, Wanfang Medical Network and CNKI databases were searched for RCT studies on AF screening efficacy using wearable devices, published from establishment of the databases to October 30, 2021. The data related to AF detection rates were extracted, summarised and analysed according to "Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses". Results A total of 11 RCT papers with a total of 41 565 intention-to-screen participants were identified. On continuous ECG(cECG) patches, 5 RCTs showed significantly higher AF detection rates compared with conventional detection methods. Of 6 RCT studies on handheld intermittent ECG detection devices, only 2 showed significantly higher AF detection rates compared with conventional methods. Conclusion AF can be more effectively screened using continuous cECG-based wearable devices compared with conventional detection methods. The effect of handheld intermittent ECG devices on AF screening was inconsistent, and further research is needed. -

Key words:

- Wearable devices /

- Atrial fibrillation /

- Screening /

- Randomised controlled trials /

- Systematic review

-

表 1 可穿戴设备用于房颤筛查的RCT研究汇总

Table 1. Summary of RCT studies on AF screening using wearable devices

首位作者,发表年,国家 筛查方法干预组vs. 对照组 研究对象;人数,平均年龄;随访时间 可穿戴设备监测持续时间 干预组房颤判定标准 房颤检出率(干预组/对照组, %) 房颤检出率相对比 检出率比较的P值 KAURA A, 2019, 英国[6] Zio Patch vs. 24-h Holter 过去72 h内被诊断为非腔隙性卒中或TIA的患者;干预组43人,70.7岁;常规检测手段对照组47人, 70.0岁;随访90 d 连续14 d ≥30 s房颤 16.3/2.1 7.76 0.03 OKUBO Y, 2022, 日本[7] myBeat vs. 24-h Holter ≥65岁合并房颤高危因素、无房颤既往病史的出院患者;干预组150人,73.9岁;14 d内常规检测手段对照组150人, 72.9岁 连续5 d ≥30 s房颤 10.7/4.7 2.28 0.04 HA A C T, 2021,加拿大[8] SEEQ或CardioSTAT vs. 12导ECG或24-h Holter 心脏外科术后出院患者,术前无房颤、房扑病史;干预组163人,67.5岁;常规检测手段对照组173人,67.4岁;30 d随访 连续28~30 d 累计≥6 min的房颤或房扑 19.6/1.7 11.53 < 0.01 STEINHUBL S R, 2018, 美国[9] Zio patch vs. 常规12导ECG ≥75岁、或≥55岁男性或≥65岁女性合并房颤高危因素、无房颤既往病史的健康保险参加者;干预组1 366人,73.5岁;常规检查组1 293人,73.1岁;4个月随访 开始时和3个月时各连续14 d ≥30 s的房颤或心扑 3.9/0.9 4.33 < 0.05 GLADSTONE D J,2021,加拿大[10] Zio Patch vs. 12导ECG ≥75岁合并高血压、无房颤既往病史的社区居民;干预组434人,79.8岁;常规检测手段对照组422人,80.1岁;6个月随访 开始时和3个月时各连续14 d 累计≥5 min的房颤或房扑 5.3/0.5 10.60 < 0.01 HALCOX J P J, 2017, 英国[11] AliveCor Heart Monitor vs. 24-h Holter ≥65岁无房颤病史、CHADS-VASc≥2、无既往房颤病史的患者;干预组500人,72.6岁;常规检测手段对照组501人,72.6岁;12个月随访 每周2次检测,各30 s;共12个月 ≥30 s房颤 3.8/1.0 3.80 < 0.05 KOH K T, 2021, 马来西亚[12] AliveCor KardiaMobile vs. 24-h Holter ≥55岁、过去12个月有缺血性卒中或TIA、无既往房颤病史的患者;干预组105人,65.3岁;常规检测手段对照组98人,65.8岁;3个月随访 每天3次检测,各30 s;共30 d ≥30 s房颤 9.5/2.0 4.75 0.02 GOLDENTHAL I L, 2019, 美国[13] AliveCor KardiaMobile vs. 24-h Holter 消融或复律后的患者;干预组115人,61岁;常规检测手段对照组118人,61岁;6个月随访 平均每天1次检测(30 s);共6个月 ≥30 s房颤 50.4/41.5 1.21 0.17 MANCINETTI M, 2021, 瑞典[14] Zenicor单导ECG检测器vs. 常规12导ECG ≥18岁无房颤病史的普通内科住院患者;干预组381人,66.2岁;常规检测手段对照组423人,64.6岁;6 d住院期间观察 每天2次检测,各30 s,共6 d ≥30 s房颤 1.8/0.7 2.57 0.20 KAASENBROOD F, 2020,荷兰[15] MyDiagnostick单导ECG检测器vs. 常规12导ECG 全科诊所中≥65岁无房颤病史的常规患者;干预组8 581人,74.3岁;常规检测手段对照组8 526人,74.5岁;随访1年 1年内在诊所就诊时的机会性筛查 ≥30 s房颤 1.43/1.37 1.04 0.73 UITTENBOGAART S B, 2020, 荷兰[16] MyDiagnostick单导ECG检测器vs. 常规12导ECG 全科诊所中≥65岁无房颤病史的常规患者;干预组8 874人,75.2岁;常规检测手段对照组9 102人,75.0岁;随访1年 1年内在诊所就诊时的机会性筛查 ≥30 s房颤 1.6/1.5 1.06 0.60 表 2 根据RoB 2工具对随机临床试验进行偏倚风险评价

Table 2. Risk of bias assessment of randomized clinical trials according to RoB 2.0

第一作者 随机过程的偏倚 偏离既定干预的偏倚 结局数据缺失的偏倚 结局测量的偏倚 结果选择性报道的偏倚 整体偏倚a KAURA A[6] L M M L L M OKUBO Y[7] M M L L L M HA A C T[8] L M L L L M STEINHUBL S R[9] L M L L L M GLADSTONE D J[10] L M L L L M HALCOX J P J[11] L M L L L M KOH K T[12] L M L L L M GOLDENTHAL I L[13] L M L L L M MANCINETTI M[14] L M L L L M KAASENBROOD F[15] L M H L L H UITTENBOGAART S B[16] L M H L L H 注:L为低风险,M为可能存在风险,H为高风险。a表示如果5个模块中任一个模块被评为“高风险”,或多个模块被评为“可能存在风险”且对研究结果的可信度有较大影响,则整体评价为高风险;如果5个模块的偏倚评估均为低风险,则总体偏倚风险评价为低风险;如果5个模块均未被评为高风险,但有任一模块被评为可能存在风险,则整体评价为可能存在风险。 -

[1] CURRY S J, KRIST A H, OWENS D K, et al. Screening for atrial fibrillation with electrocardiography: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement[J]. JAMA, 2018, 320(5): 478-484. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.10321 [2] 刘露, 刘晓宇. 全科医生在心房颤动综合管理中的作用[J]. 中华全科医学, 2021, 19(9): 1553-1556. doi: 10.16766/j.cnki.issn.1674-4152.002110LIU L, LIU X Y. Role of general practitioners in the integrated management of atrial fibrillation[J]. Chin J General Practice, 2021, 19(9): 1553-1556. doi: 10.16766/j.cnki.issn.1674-4152.002110 [3] BIERSTEKER T E, SCHALIJ M J, TRESKES R W. Impact of mobile health devices for the detection of atrial fibrillation: Systematic review[J]. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth, 2021, 9(4): e26161. DOI: 10.2196/26161. [4] MOHER D, LIBERATI A, TETZLAFF J, et al. Preferred reporting items for ssystematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement[J]. J Clin Epidemiol, 2009, 62(10): 1006-1012. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.005 [5] 刘括, 孙殿钦, 廖星, 等. 随机对照试验偏倚风险评估工具2.0修订版解读[J]. 中国循证心血管医学杂志, 2019, 11(3): 284-291. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-PZXX201903006.htmLIU K, SUN D Q, LIAO X, et al. Interpretation of revised version 2.0 of the Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for Randomized Controlled Trials[J]. Chin J Evid Based Cardiovasc Med, 2019, 11(3): 284-291. https://www.cnki.com.cn/Article/CJFDTOTAL-PZXX201903006.htm [6] KAURA A, SZTRIHA L, CHAN F K, et al. Early prolonged ambulatory cardiac monitoring in stroke (EPACS): An open-label randomised controlled trial[J]. Eur J Med Res, 2019, 24(1): 25-34. doi: 10.1186/s40001-019-0383-8 [7] OKUBO Y, TOKUYAMA T, OKAMURA S, et al. Evaluation of the feasibility and efficacy of a novel device for screening silent atrial fibrillation (MYBEAT trial)[J]. Circ J, 2022, 86(2): 182-188. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-20-1061 [8] HA A C T, VERMA S, MAZER C D, et al. Effect of continuous electrocardiogram monitoring on detection of undiagnosed atrial fibrillation after hospitalization for cardiac surgery: A randomized clinical trial[J]. JAMA Netw Open, 2021, 4(8): e2121867. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.21867. [9] STEINHUBL S R, WAALEN J, EDWARDS A M, et al. Effect of a home-based wearable continuous ecg monitoring patch on detection of undiagnosed atrial fibrillation: The mSToPS randomized clinical trial[J]. JAMA, 2018, 10(2): 146-155. [10] GLADSTONE D J, WACHTER R, SCHMALSTIEG-BAHR K, et al. Screening for atrial fibrillation in the older population: A randomized clinical trial[J]. JAMA Cardiol, 2021, 6(5): 558-567. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2021.0038 [11] HALCOX J P J, WAREHAM K, CARDEW A, et al. Assessment of remote heart rhythm sampling using the AliveCor heart monitor to screen for atrial fibrillation: The REHEARSE-AF study[J]. Circulation, 2017, 136(19): 1784-1794. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030583 [12] KOH K T, LAW W C, ZAW W M, et al. Smartphone electrocardiogram for detecting atrial fibrillation after a cerebral ischaemic event: A multicentre randomized controlled trial[J]. Europace, 2021, 23(7): 1016-1023. doi: 10.1093/europace/euab036 [13] GOLDENTHAL I L, SCIACCA R R, RIGA T, et al. Recurrent atrial fibrillation/flutter detection after ablation or cardioversion using the AliveCor KardiaMobile device: IHEART results[J]. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol, 2019, 30(11): 2220-2228. doi: 10.1111/jce.14160 [14] MANCINETTI M, SCHUKRAFT S, FAUCHERRE Y, et al. Handheld ECG tracking of in-hospital atrial fibrillation (HECTO-AF): A randomized controlled trial[J]. Front Cardiovasc Med, 2021, 8: 681890. DOI: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.681890. [15] KAASENBROOD F, HOLLANDER M, DE BRUIJN S H, et al. Opportunistic screening versus usual care for diagnosing atrial fibrillation in general practice: A cluster randomised controlled trial[J]. Br J Gen Pract, 2020, 70(695): e427-e433. doi: 10.3399/bjgp20X708161 [16] UITTENBOGAART S B, VERBIEST-VAN G N, LUCASSEN W A M, et al. Opportunistic screening versus usual care for detection of atrial fibrillation in primary care: Cluster randomised controlled trial[J]. BMJ, 2020, 370: m3208. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.m3208. [17] QUER G, FREEDMAN B, STEINHUBL S R. Screening for atrial fibrillation: Predicted sensitivity of short, intermittent electrocardiogram recordings in an asymptomatic at-risk population[J]. Europace, 2020, 22(12): 1781-1787. doi: 10.1093/europace/euaa186 -

下载:

下载: